Public Trust and the Psychology of Transparency in Policing: Why Honesty Is the New Currency

By Parth B. · ~26 min read

Public trust in law enforcement has been on a steady decline in the United States, reaching historic lows in recent years. High-profile incidents of police misconduct, often captured on video, have fueled public perception that policing is sometimes biased or unjust. According to Gallup polling, confidence in the police nationwide fell from 53% in 2019 to just 48% in 2020 – the lowest level in decades – before modestly rebounding to 51% in 2021. The decline in trust has been most severe among Black Americans: surveys found less than 20% of Black respondents expressed confidence in the police in 2020. Such statistics underscore a legitimacy crisis – a growing portion of the public doubts whether police authority is exercised fairly and lawfully. [Source]

This mistrust has profound consequences for public safety and the social fabric. When citizens do not trust the police, they are less likely to report crimes, come forward as witnesses, or cooperate in investigations. They may even be less likely to comply with lawful orders, as cynicism and fear replace respect. Indeed, research shows that when trust and legitimacy erode, people become more hostile to police and less willing to obey the law, undermining safety for everyone. In short, legitimacy is the lifeblood of effective policing. As the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing noted, decades of research indicate that "people are more likely to obey the law when they believe that those who are enforcing it have authority that is perceived as legitimate". And crucially, "the public confers legitimacy only on those whom they believe are acting in procedurally just ways". This finding highlights that legitimacy comes not from sheer authority or force, but from the fair and ethical conduct of police officers. [Source]

Amid calls for police reform and increased accountability, a central theme has emerged: honesty and transparency are the new currency of trust. If police wish to regain public confidence, they must engage the community with openness – clearly communicating their intentions, admitting mistakes, and demonstrating accountability. This article explores the social science behind transparency and trust in policing. We delve into how openness, honest communication, and even apologies can powerfully influence public perceptions of police legitimacy and encourage cooperation. The goal is to educate and inform readers on why honesty is not just a moral virtue in policing, but a practical necessity to foster safer communities. By examining the latest research and real-world examples, we hope to illuminate how a culture of transparency can improve police-community relations and serve the public good. [Source]

Understanding Legitimacy: Why Trust Matters

In a democracy, law enforcement's authority is ultimately granted by the people. Legitimacy in policing refers to the public's belief that the police are entitled to exercise power and that their actions are morally justified and appropriate. When people view police as legitimate, they are more likely to comply with laws and cooperate with officers, even when no one is watching. On the other hand, if the public sees the police as dishonest, opaque, or unjust, that legitimacy erodes and compliance wanes. As one veteran sheriff explained, fair and effective policing are both "absolutely necessary" because they form the foundation of public trust, confidence in the police, and public cooperation with police efforts. If either perceived fairness or effectiveness falters, "policing will lose respect, trust, and public support". In essence, trust is not a "nice-to-have" bonus for police – it is essential to the core function of keeping communities safe. [Source]

Research in criminology and psychology has consistently found that procedural justice is key to building legitimacy. Procedural justice means that authorities make decisions in a fair, transparent manner and treat people with dignity and respect throughout an encounter. When officers explain their actions, listen to people's concerns, and behave neutrally and respectfully, individuals are more likely to feel the process was fair – regardless of the outcome of the interaction. This sense of fair treatment translates into greater trust in police. Studies show that perceptions of procedural fairness strongly predict whether people view the police as legitimate. In fact, community perceptions that local officers behave fairly have a larger influence on judgments of police legitimacy than even crime rates or personal experiences. [Source]

Transparency is deeply intertwined with procedural justice. One of the core components of procedural fairness is openness – people want to understand why officers take certain actions and to see that those actions align with consistent principles. Lack of transparency breeds suspicion. For example, if police stop someone without explaining the reason, the person may assume they were targeted arbitrarily or due to bias, rather than for a legitimate cause. On the other hand, when officers clearly communicate their purpose and reasoning, it demystifies the interaction and can reassure the person that they are being treated above-board. Openness in policing means shedding light on decision-making processes, policies, and behaviors so that the community is not left in the dark about how and why things happen.

Beyond individual encounters, transparency on an institutional level – such as sharing information about department policies, use-of-force incidents, or disciplinary actions – also contributes to legitimacy. A police agency that willingly discloses both its successes and its failures is signaling that it has nothing to hide, that it welcomes scrutiny, and that it holds itself accountable. This can contrast sharply with agencies that reflexively stonewall or obscure information after contentious incidents, which often deepens public mistrust. As the 2015 Task Force on 21st Century Policing recommended, agencies should "establish a culture of transparency and accountability to build public trust and legitimacy". When the community is kept informed and decision-making is understood, people are more likely to accept police actions as aligned with policy and the public interest. [Source]

Trust matters because it undergirds every aspect of public safety. Trust makes people more likely to obey laws and cooperate with officers. It also improves officer safety – citizens who trust police are far less likely to respond with hostility or violence. And trust is fragile: it can be eroded by each incident of misconduct or perceived injustice, especially in an age where videos virally expose lapses in integrity. Building and maintaining legitimacy requires consistent fairness, openness, and honesty in all police operations. The following sections explore how specific practices – from everyday communication to public apologies – can bolster trust or, if mishandled, further undermine it. [Source]

A Bellevue Police officer engages with a community member during a "Coffee with a Cop" event in downtown Bellevue. These informal gatherings provide opportunities for residents to connect with local law enforcement in a relaxed setting, strengthening community-police relations.

Photo credit: Bellevue, WA Police Department | Source: Facebook.com/BellevuePolice

Openness in Everyday Encounters: The Power of Communication

Every police-citizen interaction is a building block of trust. For the person interacting with an officer, that moment may shape how they view law enforcement for years to come. Even a routine encounter like a traffic stop or a street conversation can leave a lasting impression of either fairness or intimidation. Recognizing this, progressive police training increasingly emphasizes communication skills and transparency at the street level. Something as simple as an officer clearly stating why they are approaching someone can dramatically alter the tone of an encounter.

Recent groundbreaking research has demonstrated the powerful effect of a brief transparency statement at the start of a police interaction. In a 2025 field experiment published in Nature Communications, officers on community patrol were instructed to begin conversations with a friendly explanation of their purpose – for example: "Hello, I'm Officer ____. I'm walking around trying to get to know the community". This one-sentence statement of benevolent intent, delivered at the outset, led community members to report feeling less threatened and significantly greater trust toward the officer. In the study, 232 community members were randomly assigned to interact with officers who either used the transparency statement or did not. Those who heard the upfront explanation of a positive purpose felt more at ease and trusting during the encounter. Objective measures supported these self-reports – for instance, participants' physiological stress responses were lower when the officer had communicated their benign intentions. [Source]

This finding aligns with common sense: if you know why an officer is talking to you and that it's not because you're suspected of wrongdoing, your guard goes down. Yet traditionally, many police interactions – even so-called "community policing" stops – start with the officer asking questions in an investigative tone ("Where are you going? What are you doing here?") without explaining themselves. The research team, who spent hundreds of hours observing police-community interactions, noted that officers often fail to leverage their discretion in a way that builds trust. Instead of immediately signaling goodwill, they default to a curt, authority-driven style that residents find threatening. Community members commonly assume, "The only reason an officer would approach me is to suspect or catch me doing something wrong." This assumption triggers anxiety and defensiveness. In the observed cases, civilians frequently tried to disengage or shrink away, which officers sometimes misinterpreted as suspicious behavior – a dynamic that could needlessly escalate a benign encounter into a tense one. [Source]

The "transparency statement" intervention breaks that negative cycle by immediately clarifying the officer's benevolent intent. By explicitly stating they are there to connect, not to accuse, officers can prevent the civilian from jumping to the worst-case assumption. The Nature study showed that when some officers used this approach, "community members appeared at ease and willing to talk," whereas with the traditional approach others took, citizens felt harassed and tried to flee the conversation. In essence, a few words of openness at the start bought a reservoir of trust. [Source]

These results are striking because they suggest that improving police-community relations doesn't always require grand policy changes or years of effort – sometimes it's about the micro-behaviors in daily interactions. Training officers to communicate more openly and humanely can make a measurable difference. Community policing programs have long asserted that officers should build relationships, but this research pinpointed how: by communicating your purpose honestly and early, you set a cooperative tone. Notably, the benefit of transparency statements in the study cut across racial and socioeconomic lines; even members of historically over-policed groups responded positively when officers were upfront about their intentions. This indicates transparency is a universally effective tool for trust-building. [Source]

Beyond the initial greeting, transparent communication throughout an encounter is important. For example, during a traffic stop, an officer who politely explains the reason for the stop ("I pulled you over because your brake light is out") will likely find the driver less anxious or resentful than if they gave no explanation. Explaining what action the officer will take ("I'm going to run your license, sit tight") also keeps the citizen informed and shows respect for their understanding. Many departments now train officers to use scripts that include these elements of explanation and reassurance. Such practices map onto the concept of "verbal judo" or tactical communication, which aims to gain voluntary compliance through words rather than force.

Communication matters not only for the person being stopped but also for community onlookers or later observers. In the smartphone era, any police interaction might be recorded and shared. When bystanders see a video of an officer calmly explaining and treating someone with courtesy, it can improve general perceptions of police. On the other hand, footage of an officer barking orders with no explanation can harm public confidence even if the underlying stop was legally justified. In this way, every interaction is a public relations moment for policing. Openness and courtesy have a ripple effect, influencing not just the directly involved citizen but the broader community's trust.

The psychology of transparency in face-to-face encounters is clear: uncertainty breeds mistrust, while communication breeds understanding. Police officers hold a great deal of discretionary power in these moments – the power to choose a tone of openness or one of cold authority. By consciously choosing transparency and clear communication, officers can signal respect and good faith. This pays dividends in the form of citizens who feel less threatened and more trusting of police motives. Over time, multiplying these small positive encounters can help repair the frayed relationship between police and the public. [Source]

A Des Moines Police officer shares a friendly moment with neighborhood children during National Night Out. This annual event brings together law enforcement and residents across more than 20 neighborhood associations to strengthen community bonds and promote public safety partnerships.

Photo credit: Des Moines Police Department | Source: Instagram.com/desmoinespolice

The Role of Apologies and Accountability: Admitting Mistakes to Restore Trust

Even in the best police agencies, things will go wrong – an officer uses poor judgment, a wrong is done to a civilian, or an entire community suffers from historical injustices. How law enforcement responds in the aftermath of mistakes or misconduct can profoundly influence public trust. Traditionally, police departments have been reluctant to apologize or admit fault, fearing legal liability or a loss of authority. However, emerging evidence suggests that the refusal to acknowledge wrongdoing may cause greater damage to public trust than the wrongdoing itself. In contrast, sincere apologies and expressions of accountability can help maintain or restore trust after adverse events. [Source]

An apology, when warranted, is powerful because it meets a basic psychological need for recognition of harm. Community members want their hurt or outrage to be acknowledged. When police leaders or officers say, "We made a mistake, and we are sorry," it validates the community's feelings and signals that the agency holds itself to ethical standards. A column in the International Association of Chiefs of Police magazine put it bluntly: "Most agree that public officials would be better off if they simply admitted their transgressions, apologized, and sought forgiveness." Trying to cover up errors or adopt a "never admit fault" stance often backfires. It can breed cynicism and anger greater than the original incident, as people feel they are being lied to or that authorities don't care about harm caused. Indeed, some forward-thinking law enforcement agencies have even developed standard operating procedures for using apology and regret as tools of risk management and trust-building. [Source]

However, not all apologies are created equal. The content and sincerity of the apology determine whether it heals or backfires. Research on reconciliation efforts between police and communities shows that a "partial" or insincere apology can be worse than no apology at all for those already predisposed to distrust the police. Specifically, experimental studies have found that apologies which fail to acknowledge the police's responsibility for past harms actually reduced the willingness to cooperate among Black Americans who distrusted police, compared to receiving no apology message. In other words, when an apology sounds like a hollow "we regret things happened" without taking ownership, it can deepen cynicism. For these skeptical community members, a defensive or equivocal apology was interpreted as just more empty rhetoric – reinforcing their belief that the police refuse to truly change or hold themselves accountable. [Source]

By contrast, when authorities fully acknowledge wrongdoing and take responsibility, an apology can open the door to forgiveness and cooperation. In one prominent case, a Georgia police chief in 2017 publicly apologized for a lynching that had occurred in his town decades earlier, explicitly labeling it as an injustice. Such gestures, though symbolic, carry weight in showing communities that police leadership is willing to confront historical wrongs rather than sweep them under the rug. They set a tone that police agencies are committed to moral reckoning. Psychological studies on intergroup apologies (such as apologies from a government or organization to a harmed group) indicate that perceived sincerity is the linchpin: victims are moved by apologies only if they believe the remorse is genuine and accompanied by a change in behavior. A checklist for a meaningful apology typically includes: a clear statement of responsibility ("we were wrong"), an expression of regret or remorse ("we are deeply sorry"), acknowledgment of the harm caused, and often an explanation of steps to prevent it from happening again. [Source]

In policing, that last element – the plan of action for the future – is crucial. An apology that is purely words with no indication of reform can ring hollow. A 2024 study in the Journal of Experimental Criminology tested this by presenting people with scenarios of a police department apologizing after a wrongdoing. Some were given just an apology, others an apology plus a concrete reform plan (such as new training or policy changes to ensure the mistake isn't repeated). The result: people were significantly more willing to cooperate with police when the apology included a plan of action for the future. This effect was especially strong among participants who initially had negative views of police fairness. In essence, a community member skeptical of police might think, "I've heard apologies before – why should this time be different?" But if the apology is coupled with a specific commitment like "we will implement bias training and oversight to make sure this doesn't happen again," it lends credibility. It shows the agency is not just checking a public relations box but is serious about change. [Source]

The takeaway for law enforcement leaders is that honesty coupled with accountability can disarm even hardened critics. For example, after an unjustifiable use of force incident, a police chief who swiftly acknowledges it was wrong, suspends the officer, and announces a review or reform can prevent the total breakdown of community relations. On the other hand, a chief who stays silent or reflexively defends the indefensible may find their community in upheaval and distrust deepening. We saw this during events like the 2020 murder of George Floyd – initially, there was anger that the involved officers were not immediately arrested or condemned by authorities, which led to explosive protests. Transparency and accountability (eventually the officers were charged and officials acknowledged wrongdoing) were necessary steps to begin rebuilding trust, although in that case the enormity of the event meant trust was deeply shattered.

It's worth noting that apologizing or admitting fault is not only ethically right; it also has practical benefits in reducing legal fallout. Some research has found that apologies by public officials can even reduce the likelihood of lawsuits or the size of settlements, as victims may feel some sense of closure or goodwill from the apology [Source]. Of course, police departments must navigate these situations carefully, often with legal counsel's input. But the old mantra of "never apologize, never explain" is increasingly seen as counterproductive in an era where the public demands transparency and ethical conduct from its institutions.

Honesty after mistakes is a critical test of an institution's integrity. For police agencies, being transparent about errors, rather than burying them, can ultimately strengthen their relationship with the community. Apologies, done right – with sincerity and follow-through – are a tool for reconciliation. They send the message that police exist to serve the people, and when they fall short, they owe the people the truth. Such gestures can start to heal wounds and rebuild some measure of trust, especially in communities that have long histories of fraught police relations.

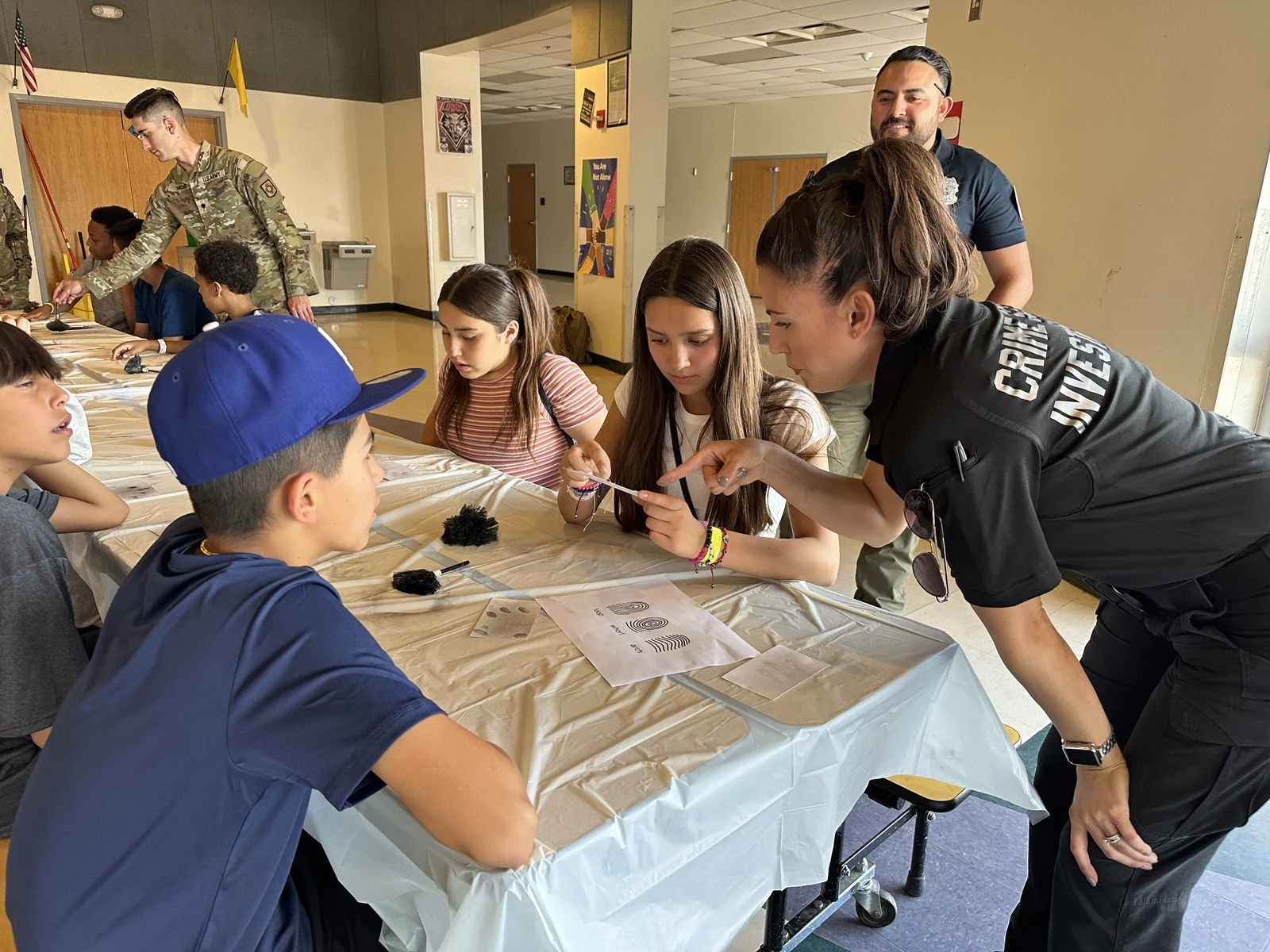

Albuquerque Police Department officers engage with youth participants during the annual Camp Fearless summer program. The week-long camp provides children ages 8-13 with hands-on learning experiences about law enforcement careers while building positive relationships between officers and young community members.

Photo credit: Albuquerque Police Department | Source: cabq.gov/police

Building a Culture of Transparency: From Policy to Practice

While individual officer actions and leadership apologies are important, making honesty the "new currency" in policing requires a broader cultural shift within law enforcement. Transparency should not be an occasional performance – it needs to be baked into the policies, practices, and ethos of police organizations at every level. This means rethinking traditional norms of secrecy and defensiveness that have pervaded policing for generations.

One aspect of a transparent culture is how a department handles information and data. In the past, police may have treated data on stops, arrests, uses of force, or complaints as internal matter, releasing little to the public. Today, many agencies are embracing open data initiatives as a form of public transparency. By proactively publishing statistics on traffic stops or releasing body camera footage of critical incidents, departments aim to demystify their operations and invite community oversight. For instance, some cities have online dashboards where anyone can view updated data on police-citizen encounters, use-of-force incidents, or disciplinary outcomes. This level of openness can improve public trust by showing that the department has nothing to hide and is willing to hold itself accountable with evidence. A report by the Bureau of Justice Assistance noted that sharing information – even when it reflects problems – can increase community cooperation by proving that police and community are on the same team, working from a basis of facts [Source].

Another element is external oversight and communication. Departments that foster transparency often establish robust channels for community feedback and independent review. This can include civilian oversight boards that review misconduct cases, or community meetings where police officials share updates and take tough questions from residents. When law enforcement leaders engage in dialogue and actively listen to community concerns, it humanizes both sides and breaks down the "us vs. them" mentality. It shows humility – a recognition that police can learn from the public and must earn their trust, not demand it unconditionally.

Technology is also playing a role in the push for transparency. The widespread adoption of body-worn cameras in the last decade was largely driven by a public desire for more honest documentation of police encounters. Body cameras are seen as tools that can increase accountability and transparency by providing an objective record of what happened. When used properly, they can protect both civilians and officers from false allegations. However, the impact of body cameras on trust depends on policies about when the footage is released and how it is used. If a critical incident occurs (like a police shooting) and the department swiftly releases the bodycam video, it can prevent misinformation and show a commitment to transparency. If instead the department withholds footage for months, public suspicion often grows. Research on body cameras shows mixed results on behavior, but many departments credit them with reducing complaints and uses of force. At minimum, they are now an expectation – the public feels that seeing is believing, and having a video record is part of accountable policing. [Source]

Transparency must also extend within the department, not just outwardly. An internally transparent agency encourages officers to speak up about problems, admit mistakes without fear of undue punishment, and share information across units. This kind of open internal culture can prevent small issues from festering into big scandals. It's analogous to aviation, where a culture of reporting near-misses and errors has improved safety; policing can benefit from a culture where integrity and truthfulness are valued over a cover-your-backside mentality. Whistleblower protections, anonymous surveys of officer morale and ethics, and strong leadership messaging on honesty can all reinforce this.

Leadership is perhaps the most critical factor. If top brass model transparency – by being forthright with crime statistics, admitting when strategies aren't working, and communicating both good and bad news – it sets the tone for the whole agency. Conversely, if leaders are secretive or retaliate against those who air problems, the rank-and-file will get the message that transparency is just lip service. Many chiefs now embrace the idea of a "guardian mindset" rather than a "warrior mindset," emphasizing service, empathy, and transparency as core values. This aligns with the Task Force recommendation to adopt procedural justice as a guiding principle both externally and internally. When officers feel they are treated transparently and fairly by their own organization, they are more likely to pass on that respectful treatment to the public. [Source]

There are challenges to embedding transparency. Police officers often operate in a culture of control and command, where admitting uncertainty or mistakes goes against the grain. It takes training and positive reinforcement to show officers that transparency is not a weakness but a strength. Additionally, there can be institutional inertia or fear – concern that being too open will invite criticism or lawsuits. However, the trend in modern policing is unmistakable: the expectation of transparency is here to stay, and agencies that embrace it tend to fare better in public opinion than those that do not. In an age of social media and immediate information, trying to suppress or spin the truth is a losing battle. Instead, owning the narrative by being honest and proactive is the smarter long-term strategy for building trust.

Ultimately, a culture of transparency is about aligning policing with its public service mission. It recognizes that police derive their authority from community trust, and thus the community has a right to know how that authority is used. By institutionalizing honesty – whether through community engagement, open data, or candid leadership – policing can gradually replenish the well of public goodwill.

A Colorado Springs Police officer stands with Joe Joseph, one of the department's longest-serving Neighborhood Watch Block Captains since 1994. Mr. Joseph exemplifies community-police partnership through decades of volunteer service, including personally funding and installing neighborhood watch signs during the city's financial crisis.

Photo credit: Colorado Springs Police Department | Source: Facebook.com/cspdpio

Honesty as the New Currency: Earning Trust, Enhancing Safety

The phrase "honesty is the new currency" in policing encapsulates a simple truth: in today's environment, trust must be earned, and the coin of that realm is transparency. Gone are the days when a badge and a uniform automatically commanded public deference. The American public, diverse and rightly assertive of its rights, now scrutinizes police conduct more closely than ever. The only sustainable way for law enforcement to secure willing cooperation is by demonstrating that they operate with integrity, openness, and a genuine commitment to fairness.

What are the dividends of investing in honesty? First and foremost, public cooperation. Communities that trust their police are more likely to report crimes, provide tips, and work as partners in public safety. One study noted that when community members trust and feel safe around police, they are more likely to help de-escalate situations and even intervene to assist officers, creating a virtuous cycle of safety [Source]. Cooperation also extends to compliance – people are far more prone to comply with laws and police directives when they view the source as legitimate and just. This means fewer instances of resistance or confrontation and a smoother path to conflict resolution. In effect, trust can serve as a force multiplier for law enforcement, doing some of the work that fear or coercion might otherwise try (and fail) to accomplish.

Second, honesty and transparency can reduce tension and fear in communities. In many high-crime neighborhoods, a lack of trust leads to a climate of mutual suspicion – residents fear harassment and officers fear hostility. Transparency breaks this down by replacing rumor and speculation with information. If a spate of robberies is occurring and police openly communicate what they are doing to solve it (and what they need from the community), residents feel included and less afraid, rather than being left in the dark under a heavy police presence. Likewise, when an incident happens and the police quickly share what they know (instead of clamming up), it can prevent misinformation from inciting anger. Transparency is, in a sense, preventative medicine against unrest. Many clashes between police and protesters over the years have been exacerbated by poor communication – by contrast, when authorities have been proactive and transparent (for example, quickly acknowledging an officer-involved shooting and releasing details), communities have sometimes responded with more patience and calm while due process unfolds.

Another benefit is improved officer morale and performance. It may seem counterintuitive, but when the public trusts police more, it directly improves the work environment for officers. They face fewer hostile encounters, receive more cooperation, and often feel safer. It's notable that in recent years, amid public distrust, many police departments have struggled with recruitment and retention. A climate of mistrust and negativity makes the job less attractive and burns out current officers. By rebuilding trust, law enforcement agencies can ease some of that strain. Officers who feel respected by the community are more likely to take pride in their work and less likely to adopt an "us versus them" mentality. In this way, transparency and legitimacy benefit not just civilians but police professionals as well – it is a two-way street where trust and respect flow in both directions. [Source]

To be clear, championing honesty in policing is not about being "soft" on crime or endlessly accommodating unreasonable public demands. It is about smart policing – recognizing that trust and legitimacy are among the most powerful tools for achieving compliance and public safety. When communities see officers as guardians of justice rather than as an occupying force, they grant them the moral authority to do their jobs effectively. On the other hand, if police are seen as opaque or untruthful, every action they take is eyed with suspicion, even the well-intentioned ones. In our polarized times, transparency is a way to cut through the clouds of rumor and show the reality of policing, warts and all, and then work collaboratively to fix those warts. [Source]

Moving forward, the path to better police-community relations is illuminated by social science and lived experience: openness, accountability, and communication are indispensable. Body cameras, civilian review boards, public data releases – these are structural expressions of transparency. Equally important are the human interactions: the officer who listens and explains, the chief who faces cameras and owns up to a failure, the department that engages activists and critics in dialogue. These actions speak volumes. They tell the public, "We exist for you, and we have nothing to hide. Your trust is our most valued asset."

Honesty is indeed the new currency in policing because legitimacy cannot be bought with force or authority – it must be paid for with truthfulness and respect. Rebuilding trust in American policing will take time and consistent effort, but each transparent policy, each ethical decision, each sincere apology and open conversation deposits a bit more goodwill into the bank of public trust. And as that trust grows, so too does the safety and cohesion of our communities. In a very real sense, everyone wins: citizens feel respected and protected, and police can do their jobs more effectively with the community by their side rather than at their throats. Transparency and honesty are not just PR strategies; they are the lifelines of democratic policing. By embracing them, we move closer to the ideal of a policing system that is both just and effective – one where the badge is backed not just by legal authority, but by the proud consent of the people it serves.